.jpg) |

| Basilica San Clemente, Rome: what you see is not all you get. |

About half a kilometre from the Roman Coliseum is an crumbling old basilica dedicated to Pope Clemente I. It was built in the twelfth century - the Basilica San Clemente. It has some curious features, but none more curious than the fact that it is built almost precisely on top of a previous church dedicated to San Clemente.

The older church was built in the fourth century AD, and only discovered by a very curious digging monk named Fr. Joseph Mullooly who found it during the nineteenth century. He is fittingly buried beneath the altar in the preserved fourth century church.

|

| Today's church, from the monastic quadrangle. |

But there’s more. Fr. Mullooly also found other buildings below the fourth century church - three levels down are buildings from the first century AD, including Roman houses and a curious Mithraic temple, used to practice an old pagan religion based around the sacrifice of a bull by the god Apollo. In the houses, a fine clear spring still bubbles up.

Even deeper underground are indications that still older houses stood on this site, houses which were burned down in the great conflagration of the time of the Emperor Nero, in 64 AD. The level of the valley in which San Clemente lies was about sixty feet lower in the first century than it is now. After the fire of 64 AD the gutted buildings were filled in and used as foundations for the third-level houses, at a level that is roughly that of the floor of the Colosseum today. There's an interesting video about the layers here.

|

| The fourth century church, underground (held up with 19th century pillars). Fr. Mullooly is buried under the altar. |

San Clemente and his legends

|

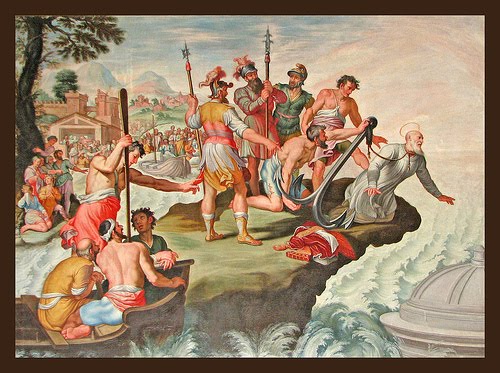

| The Legend of San Clemente. |

Very little is known about the life of St Clement who lived from 92 to101 AD. According to the oldest the basilica website.

list of Roman bishops, he was the third successor to St Peter in Rome. Check

It would take quite a while to relate all of the legends around San Clemente. There’s a story of a possibly Jewish ex-slave named Clemente who wrote a stirring letter to the Corinthians around 96 AD. All kinds of apocryphal stories grew up, including one about Clemente being banished to the Crimea in the reign of Emperor Trajan (98 - 117 AD). There he got into strife for converting everybody, and the Romans tied him to an anchor and threw him into the Black Sea. Thus, there are lots of paintings of San Clemente being tied to the anchor, and an anchor is his symbol. A variety of colourful miracles followed this martyrdom.

.jpg) |

| Sassoferrato's beautiful 'Madonna' |

Whether or not any of this happened, it did inspire the two so-called “Apostles of the Slavs”, Saints Cyril and Methodius, to search for Clemente’s body in the Black Sea. Cyril reported that they were able to “miraculously recover” the body of San Clemente, piece by piece - AND the anchor - on a small island, in January 861. These bit and pieces were brought back to Rome, and rest today under the altar in the Basilica.

In fact, the remains of St Cyril are also there, housed in a side chapel under a charming painting of the Madonna by Sassoferrato. It’s said that Cyril’s first resting place was down in the fourth-century church, and scholars think they might have located the spot - it’s marked today with a small altar. But presumably Cyril was brought upstairs when the new Basilica was built in 1110.

Reusing the old basilica

|

| Re-used marble choir; inspired mosaics. |

A few other bits and pieces were also re-used from the fourth century church when the new basilica was built, most spectacularly the large carved marble choir, or schola cantorum, where the chanting priests and acolytes would sit during service. A pair of beautiful ornate columns were also recycled from below for a marble cardinal’s tomb in the fifteenth century. Perhaps most interestingly, the gorgeous mosaics that cover the apse, the “crowning glory” of the Basilica, although executed in the twelfth century, are full of much earlier medieval imagery. My small guide book (written by one Leonard Boyle in the 1960s) says:

The motifs here are so clearly in the tradition of the fourth and fifth centuries that it has been suggested that the mosaic is simply a reproduction or, possibly, a remodelling on a smaller scale, of the mosaic that decorated the apse of the abandoned basilica below. Certainly there is the typically fourth and fifth century conception of the Cross as the new “Tree of Life” planted upon the hill of paradise restored by Christ, from which a river “divided into four heads” (Phison, Gehon, Tigris, Euphrates) flows to “water paradise” (Genesis 2, 10-14) and the whole world. Then there are the doves, symbols of souls, the hart drinking of the river, and the phoenix of immortality....

The old frescoes

The 12th century basilica has its share of frescoes. Many tell the legends of San Clemente, including the scene where he’s thrown into the sea with an anchor around his neck. There is also a lovely fifteenth century Saint Christopher on the wall, which has attracted pilgrims for centuries. Today it’s covered in protective perspex, but the pilgrims used to scratch their names on it. The oldest of these graffiti has the date 1459. There’s a side chapel covered with frescoes detailing the life, works and death of Saint Catherine of Alexandria (she of the wheel), done around 1428 to 1431 by a painter named Masolino, possibly assisted by his young contemporary Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Mone, known as' Masaccio' (which I mention because it translates to “Hulking Tom”, which conjures quite a visual image).

Down below in the fourth century church there are also, amazingly, some reasonably well-preserved frescoes and parts of frescoes. One of the very oldest is a Madonna, possibly converted from a portrait of Empress Theodora (who died in 548), the wife of Emperor Justinian. There’s faded fresco depicting the return of San Clemente's remains; a strange ‘Ascension’ (of Christ or His mother, it’s not clear); and a “Legend of St Alexis” (which appears to have been a quite exciting story.

|

| St Alexis -- it's a long story... |

There’s even a faint fresco (of a male figure) at the lower level, in the Mithraic “school”, possibly as old as the third century. How these things survive flood, mud and burial in rock, to say nothing of the passing centuries, is miraculous.

The Mithraic religion

And what went on in the Mithraeum? There’s no written records left of the Mithraic religion, only physical bits and pieces and some comments from others, so there’s a lot of guesswork involved. I’m indebted again to my little guide book for this information:

Mithras was a god born from a rock, to be the bearer of salvation, as in life and fertility, for the world. Later, at the command of the god Apollo, conveyed by a raven, Mithras set out to trap and spill the blood of the being that possessed life to the full, a Bull from the region of the Moon. In a desperate fight he manages to slay the bull, while a scorpion (personification of evil), a hound and a snake join in. From the blood of this bull all plants and all animal life and all that is good came into being, but the scorpion’s sly spilling of some of the most vital blood brought evil also into the world. When the fight was over Mithras and Apollo quarrelled, but they soon made peace, celebrating the victory with a great banquet. Then Apollo, the God of the Sun, took Mithras off to the heavens in a chariot.

|

| Mithraic dining room, with an altar from the Temple. |

From all of this, it seems that the main way of celebrating in this religion was to have great banquets. In the lower level of the San Clemente diggings there’s a fine Mithraic dining room. The Bull in this myth was the symbol of fertility, and the religion was a cosmic, seasonal one. The banquets and ceremonies usually took place underground, in grottoes. Stars were often painted on the ceiling to represent the heavens. My guide book goes on:

The religion was, in fact, severely moral, loyalty and fidelity being extolled above all else. Consecration to Mithras guaranteed salvation, for Mithras had won life for the world and was himself in heaven as reward for his obedience to the message of Apollo.

I don’t know how this strikes you, but there are some pretty strong parallels with Christianity here. My guide notes these - he’s a fair man - but becomes quite shrill in pointing out the differences. It is curious, however, that the subsequent Christian traditions should include so many aspects of an earlier pagan rite...

|

| Fr. Mullooly |

And so, layer upon layer, Basilica San Clemente tells the stories of the people who lived, survived, chose to worship, made art, and generally managed to get by overt two millennia. How amazing that we have such records of their doings. And that we can see them - thanks, Fr. Joseph Mullooly!

|

| Roman houses from the second century: there's a bright stream still running down here. |

Note: Since visitors are not permitted to take photographs in Basilica San Clemente, the images come from various sources around the web, including the website of Basilica San Clemente.

No comments:

Post a Comment